It Doesn’t Pay to Pioneer

By Charles E. Duryea, 1931 Part1

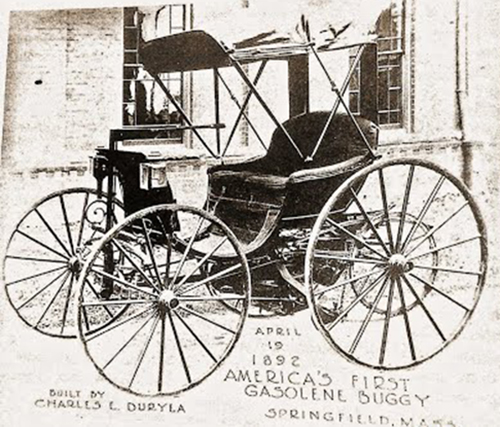

Duryea’s first gasoline-powered vehicle, operated by Him in 1892.

Duryea’s first gasoline-powered vehicle, operated by Him in 1892.

IT IS MY BELIEF that I designed and built the first gasoline automobile actually to run in America, sold the first car on this side, did the first automobile advertising and won the first two American races. The last two claims cannot be disputed; the first two have been; though no one else offers proofs acceptable in court, as I do, of operation of a gasoline vehicle as early as April 19, 1892, or sales as early as the summer of 1896.

History is a none too dependable decider of such questions. The invention of the steamboat still is disputed after more than a century, and credit is popularly given to Robert Fulton, who no more invented it than Lindbergh did the air airplane. Many men moved boats by steam before Fulton. It may even be that the twenty-first century will think of Henry Ford as the inventor of the automobile. A leader is not the man who first brings a cause to the fore, but the man who keeps it there. Until there are followers, there can be no leader.

I rest my case on the evidence, but while there is yet time I should like to read into the record the fact that most of the fundamentals of the motorcar were American-born, not European, and were demonstrated practicably a generation of more before the first horse ever bolted at the sight of a go-devil. It doesn’t pay to pioneer; not in money, at any rate. It’s the early Christian, as Saki said, who gets the fattest lion. Like my brother and my fellow pioneers, Haynes and the Appersons, C. B. King and Alex Winton, my name no longer is borne by any car.

The name of our contemporary, R.E. Olds, is perpetuated in the Oldsmobile and the Reo, though he long ago surrendered his interest in the names. Like most of them, and the inventors of the airplane, I was bicycle mechanic, and like all of them, a mechanic without technical training. There are other names that go much farther back, names that no one knows — Samuel Morey, Dr. C. G. Page, Thomas Davenport, S. Perry, W. M. Storm, Dr. A. Drake, G. B. Brayton and H. K. Shanck.

The essential elements of the modern automobile are a knuckled front axle, a multiple-cylinder, internal-combustion engine with balanced crank shaft, electric ignition, spray carburetor, throttle control coupled to a change of speed gears, transmitting power to two driving wheels through a differential, the wheels having air tires and antifriction bearings. The self-starter was not regarded as an essential until motors became much larger.

How did this engine arrive? Let us trace it’s course, keeping in mind that around it’s experimenters existed vacuum, steam and hot-air engines, but that none of these solved the problem satisfactorily. The two-cylinder, 180-degree-crank, internal-combustion engine with proppet valves, cam operated, using liquid fuel fired by a timed electric spark and vaporized in a heated carburetor — the world’s first — was patented in the United States and Great Britain in 1826 and described in two scientific journals of that year.

Duryea in the 1895 vehicle he called

“America’s first real automobile.” End of Part 1

Part 2

The Stanley twins, Francis and Freeland, in their1896 Stanley Steamer.

Samuel Morey, of New Hampshire, one of the many to operate steamboats before Fulton, was the inventor. The fuel was turpentine, of which we had a large and cheap supply. Morey tried many experiments, and by using an electric spark was able to put a compressed-burned charge above the piston before it started downward.

A decade later, Thomas Davenport, of Vermont, gave the world the rotary armature now used in starter generators, and made with it a small locomotive which he showed both in New York and London. The jump coil with it’s vibrator was made by Dr. C.G. Page, of Salem, Massachusetts, and described in a scientific publication in 1839, a dozen years before the commonly credited French inventor showed it.

Go far enough back and you will find Franklin, in 1749, firing a spoonful of spirit on the opposite bank of the Schuylkill River with an electric spark to prove that electricity could be transmitted by wire. A Professor Hare, of the University of Pennsylvania, anticipated the incandescent electric lamp in the 1820’s, using a platinum wire in nitrogen gas in an inverted drinking glass, sealed in water. Priority in invention often is a baffling thing to trace.

S. Perry, of Newport, New York, patented air and water cooled internal-combustion engines in 1843, exhibited and advertised them in New York, equipped them with self-starters in 1846. In 1851, W.M. Storm, of New York City, patented an engine which compressed the air used before ignition and employed a jump spark with engine-driven dynamo for supplying the current. He gave us modern compression a quarter of a century before Otto copied the Frenchman, De Rochas.

Doctor rake’s exhibition at the Crystal Place, New York, followed closely in 1855, showing an engine which he advocated fro locomotive use and for “vessels even to China,” because of it’s compact liquid fuel. Advertised in the Scientific American and patented abroad, it was known to Lenoir, who made several like it, using gas fuel, half a dozen years later.

George B. Brayton, of Rhode Island, appeared in 1852 and devoted the next forty years of his life to the gas engine, of which he is the real father, and had constantly in mind it’s application to horseless carriages. He gave us a new cycle of operation that ran with the certainty and sweetness of a steam engine and was related to the Diesel of recent years. One of his gasoline engines was fitted to a Providence street car in 1873 and another to a Pittsburgh omnibus in 1878, but both were denied the streets. In January, 1876, He licensed Joshua Rose and A.R. Shattuck, both men of prominence, to make road motor vehicles.

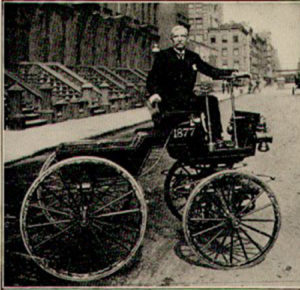

George B. Seldon in the 1877 vehicle He called “America’s first car.”

Two Brayton gas engines pumped air for the Aquarium at the Philadelphia Centennial while Otto still was showing free-piston engines in which the charge shot the piston into the air, and gravity and air-pressure on the downward stroke drove the flywheel. “The Brayton engine looked and ran like a sweetly designed steam engine, while the Otto was anything else,” said the Scientific American’s Centennial report. Otto promptly brought out his “silent,” which, because of it’s greater economy, won shop favor over the Brayton. David was not permitted to build the temple, and Brayton died in1892 without having seen the adoption of the horseless he envisaged.

End of Part 2

Part 3

In 1883, H. K. Shank was a tricycle maker at Dayton, Ohio, and began to apply gas-engine power to his machines. I saw is engine at the Ohio State Fair in 1886, the first combination of the electric spark, carburetor and liquid fuel in my experience. I recognized in it the key to the age-old problems of flight and self-propulsion, and in the next decade worked out and published a practical solution of human flight and made and proved the essentials of the successful motor vehicle.

The knuckled front axle was shown in 1818 and accredited to Akerman, of England. The differential was shown by Pecqueer, of France, in 1828. Goodyear, the American, vulcanized rubber in 1839, and Thompson, the Englishman, applied the discovery to air tires six years later. Devices for varying speed were common to many machines.

The early carburetors were not well adapted to varying speeds or volume of change, and the spray carburetor and throttle control for automobiles are believed to have been used first on a Duryea. My wife’s perfume atomizer suggested the spray carburetor to me, shortly after I had seen Shanck’s Morey device. A Duryea car made in 1894-95 was the first to use pneumatic tires, thought they already were general on bicycles. The bicycle already had ball bearings.

Electric taxicabs of 1896 looked like horseless hansom cabs.

Why was it, with the fundamentals of the motorcar and the airplane already solved, that their appearance was so long delayed? And why was the solution waived by organized industry and engineers to obscure mechanics without technical training?

Because of the weight of a unanimous and intolerant public opinion that both ideas were too silly for words, one as silly as the other–an opinion so stubbornly held that it rejected the testimony of it’s own eyes. In 1885, when I invited Samuel Bowles II, famous editor of the Springfield Republican, to ride in the Duryea which won the first American automobile race, his reply was: “I appreciate your kindness, but really, it would not be compatible with my position.” The automobile was an absurdity, wherefore it was ridiculous to be seen in one. Graduate engineers knew that flying and road transport of small vehicle were the two oldest and toughest nuts of mechanics. They knew the answers had been sought endlessly to virtually no practical result. And they were practical men, busy as trained technicians are likely to be, with routine jobs for which a demand existed.

It is a mistake to suppose that either the automobile or the airplane was created to supply a demand. The demand was very painfully built up after the machines had been proved, and many of the pioneers foundered. The reasons are three why America was destined to be the home of the automobile–great distances, scarce labor and cheap fuel. It is surprising only that the automobile was so long delayed. It was partly chance that the steam auto did not appear coincidently with the steam train. The obvious ideal of mechanical locomotion was the greatest possible freedom of movement, but when Stephenson invented his stream locomotive, it was crudely heavy, while the public roads were bad. So railroads were built especially for the locomotive. In that way the cart got before the horse. Instead of simplifying and lightening the locomotive, it was made heavier and heavier and more and more restricted to rails and a private right of way. That in turn fixed in the public mind the fallacy that no mechanically propelled vehicle belonged on the highway.

End of Part 3

Part 4

Hundreds of forgotten men, however, did operate steam road vehicles of one kind or another in the century before the automobile age dawned. Nothing came of it because of public hostility. When the automobile era finally opened, the gas car, though it led easily in performance, was the Cinderella of the trade. The electric marvels of the trolley car, the telephone and the Edison lamp had captured the public imagination. Down to 1900–even later–one of the greatest sales obstacles the gasoline car had to overcome was the general convection that any day Edison would invent a miraculous auto that would sweep the market. Next to the electric came the steam car, because of public familiarity with steam and it’s fifty years advantage in engineering practice. Steam ran the railroads, electricity the trolley cars, while the internal-combustion engine was unknown to the layman.

To the Chicago World’s Fair, in my opinion, belongs first credit for the automobile. Just as the Philadelphia Centennial sponsored the bicycle, Chicago stood godmother to the motorcar. An English high-wheel bicycle and a French steam velocipede exhibited at the Centennial in 1876 set off the bicycle craze. The Chicago Fair in 1890 and 1891 advertised throughout the world in many languages for exhibits, offering awards. One class was for “steam, electric and other road vehicles propelled by other than animal power.” Note the absence of any specific mention of the internal-combustion engine.

This at once put the problem in a new light, gave it needed dignity and prestige. A thousand experimenters who had been discouraged by ridicule ad pity took a fresh hitch at their trousers. I was one of these. What we were able to produce by 1893 was pitifully meager, but 1894 brought enough cars to permit a race in France, won by a steamer, and the next year the first American race was run at Chicago. My third car, begun late in 1893, won that race and a $2000 prize over Europe’s three entries. It was, in my judgment, the first true automobile, combining all modern essentials for the first time. Four Duryeas won all prizes, totaling $3000, in the second American race on memorial Day, 1896. The same year two Duryeas won the first British road race, London to Brighton, against the best foreign cars.

It doesn’t pay to pioneer, and yet the first American investor to put money into an automobile venture got his capital back with a profit. He was Edwin F. Markham, a nurse, of Springfield, Massachusetts. I was canvassing for funds to build our first model. Banks were out of the question, of course. The tobacconists of Springfield seemed to be prosperous and I was concentrating on them this day in the early ’90s. Markham, lounging in one shop, overheard my sales talk. In return for a tenth interest, he agreed to pay bill up to $1000. If he financed us to a self-supporting basis, he was to get a half interest. Eventually he put up $3000 and got back about $5000. He lived to see the automobile a commonplace and was very proud of his vision. End

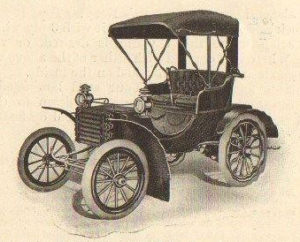

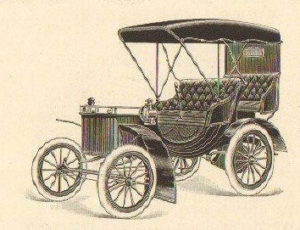

The idea of the all-purpose automobile was developed by Charles E. Duryea in 1907. The two cars advertised below are really the same car, the Duryea Phaeton. On the left it is a run about with a shelf in the rear for tying on baggage; and on the right it is a touring car with the rear seat open instead of closed and the leather top stretched back to cover both seats.

D U R Y E A—– the car with 15 years of experience in it.

We have largely increased our output for 1907, and will be in excellent position to take care of the wants of our agents. DURYEA CARS have always been Reliable, and the improvements for 1907 will make them even more satisfactory than they have been In the past This is saying a great deal, because any Duryea agent or owner will tell you that for Reliability and general utility the DURYEA Car is unexcelled.

Price, $1,550. DURYEA PHAETON, (bottom left) rear seat closed position, and, (bottom right) rear seat in the open position, with double top, the rear part of the top detachable.

This is the best automobile for the man who wants both a runabout and a touring car.

It is interchangeable by lifting the rear seat.

DURYEA POWER CO., READING, PA., U.S.A.

This article appeared in the 1984 August “Auto Echoes” monthly SIRAACA news letter,

by Sal De Francesco.